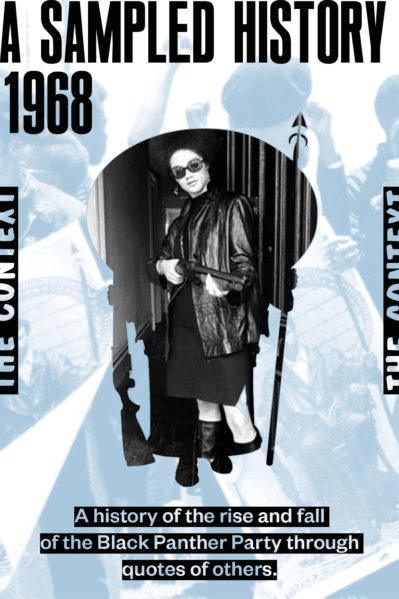

A Sampled History 1966/67, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972/82.

1968

01.1968 — “In January 1968, Eldridge Cleaver recruited Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter to organize a chapter of the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles [the first outside the Oakland Bay Area].” (Bloom 2016, 143). “When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in April, the Black Panther Party quickly became the dominant presence in the Los Angeles Black Power scene.” (Bloom 2016, 145)

01.28.1968 — “As the Black Panther Party promoted the “Free Huey!” campaign, it built on emerging alliances with students and white antiwar activists, advancing an anti-imperialist political ideology that linked the oppression of antiwar protestors to the oppression of blacks and Vietnamese. Bobby Seale elaborated this position at a January 28, 1968, rally at UC Berkeley supporting students who had been arrested during Stop the Draft Week.” (Bloom 2016, 110)

02.17.1968 — February 17, the first Free Huey Rally at the Oakland Auditorium, which presented a merger between SNCC (Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown) and Black Panther Party. “Speakers at the Huey Newton birthday celebration at the Oakland Auditorium, February 17, 1968, include, from right to left, Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, leader of the newly founded Los Angeles Black Panther Party chapter […]; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leaders James Forman, H. Rap Brown, and Stokely Carmichael; Bobby Seale; Carver Chico Nesbitt; unknown boy; and Ron Dellums. The renowned SNCC leaders were exploring a merger with the Black Panther Party at the time. The empty wicker throne highlights Newton’s absence, as he sat in prison awaiting his trial on capital charges. (© Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation)” (Bloom 2016, 167)

02.18.1968 — “[Another] “Free Huey!” rally was planned in Los Angeles on February 18, 1968 […] [by] a wide array of organizations in the Black Congress, including Karenga’s US.” (Bloom 2016, 145) “The February 18 rally drew at least five thousand people. Speakers included Bobby Seale, Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, James Forman, Ron Karenga, and radical Chicano activist Reis Tijerina.” (Bloom 2016, 145)

02.29.1968 — February 29, a memorandum of the FBI regarding “militant Black Nationalists’ was issued, which is the start of the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). The goal was “to prevent the coalition of militant black nationalist groups, prevent the rise of a leader who might unify ans electrify the violent-prone elements, prevent these militants from gaining respectability and prevent the growth of these groups among American’s youth.” (Carson in Vincent, 2013, p238).

03.1968 — “[…] Newton’s Executive Mandate No. 3, issued from prison in March 1968, ordered all Panther members to obtain firearms, and to fire on anyone — including police — who attempted to enter their homes without peaceably producing a legal warrant.” (Bloom 2016, 159-60)

03.04.1968 — “On March 4, 1968, J. Edgar Hoover expanded the COINTELPRO against black nationalists to forty-one field offices, and in a new memo established the following five long-term goals for the program.” (Bloom 2016, 202)

03.16.1968 — “In the next [March 16, 1968] issue [after the free Huey Rally of February 17, 1968] of The Black Panther, the Party dropped “for Self-Defence’ from its name and became simply the Black Panther Party.” (Bloom 2016, 114)

04.1968 — “[George Mason Murray] joining the Central Committee as minister of education by April 1968.” (Bloom 2016, 269)

04.04.1968 — “On Thursday, April 4, 1968, at 6:01 P.M., Martin Luther King Jr. stepped onto the balcony outside his second-floor room at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. […] A shot rang out, and the bullet tore through the base of the right side of King’s neck. An hour later, at 7:05, doctors at St.Joseph Hospital pronounced King dead.” (Bloom 2016, 115) “At the time of the killings of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Hutton in early April of 1968, the Black Panther Party was essentially a local organization based in Oakland, with a satellite chapter beginning to organize in Los Angeles.” (Bloom 2016, 159) “As Kathleen Cleaver later recalled, “The murder of King changed the whole dynamic of the country. That is probably the single most significant event in terms of how the Panthers were perceived by the black community.”” (Bloom 2016, 159) “While Black Power was a key influence on the emerging draft resistance movement, the Black Panther Party remained relatively insignificant politically until April 1968.” […] “This situation changed with the assassinations of King and Hutton.” (Bloom 2016, 133)

04.06.1968 — “On the evening of April 6, two days after King’s death, at a little after 9:00 p.m., three carloads of armed Black Panthers pulled over to the curb on Union and 28th Streets in largely black west Oakland. […] A moment later, several police cars pulled up and shined a spotlight on [Eldridge] Cleaver. Words were exchanged, then gunfire. The Panthers ran for cover, the police quickly cordoned off a two-block area, […]. An hour and a half later, […] Lil’ Bobby Hutton emerged from the basement unarmed. Police shot him dead.” (Bloom 2016, 119). Cleaver was also wounded during the ambush.

“But when King and Hutton were killed, a new day arrived. As the federal government inched toward establishing a national holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., Hutton became the first martyr of the Panther revolution.” (Bloom 2016, 122)

04.12.1968 — “At the April 12 funeral for Hutton, two thousand people packed into the Ephesian Church of God in Christ in Berkeley, with a hundred uniformed Black Panthers forming the honor guard. […] Seale cried out, “Free Huey!” and the crowd answered: “Free Huey!” (Bloom 2016, 119) “On April 12, 1968, SDS affirmed its support for the Black Panther Party: “Students for a Democratic Society . . . demands the immediate release of Eldridge Cleaver, Huey P. Newton, and all other political prisoners being detained by the state of California.”” (Bloom 2016, 134). “When [after attending Bobby Hutton’s funeral on April 12, 1968] the Dixon brothers [Aaron and Elmer] returned to Seattle, they rented an office and opened the first chapter of the Black Panther Party outside of California. Within two months, more than three hundred people joined the chapter, women as well as men.” (Bloom 2016, 147)

04.15.1968 — “On April 15, the cover of New Left Notes featured a photo of Bobby Hutton and a long article on the Panthers under the headline “Oakland Police Attack Panthers.” (Bloom 2016, 134)

04.1968 — “By the spring of 1968, we heard that representatives from the [Black Panther Party] were coming to New York and there was a possibility of organizing a chapter. I attended the meeting and decided to join and help build the [Party] in New York.” (Sekou Odinga in Bloom 2016, 152) “In the weeks following King’s assassination, the Black Panther Party also opened a chapter in New York City’s Harlem.” (Bloom 2016, 148) “In April, just weeks after King’s death, Joudon Ford took the reins as the new captain for the New York Black Panther Party, setting up a temporary office in the SNCC headquarters in downtown Manhattan.” (Bloom 2016, 149) “Two of the first New Yorkers to join the Black Panther Party were Lumumba Shakur, appointed section leader for Harlem, and Sekou Odinga, named section leader for the Bronx.” (Bloom 2016, 150)

“In the spring of 1968, the Black Panthers joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to begin discussions with Third World representatives in the United Nations in an effort to advance their program. The Panthers sought support for the “Free Huey!” campaign and for a proposed black plebiscite.” (Bloom 2016, 122)

05.14.1968 — “On May 14, [1968] Kathleen Cleaver announced Eldridge [Cleaver]’s candidacy for the Peace and Freedom Party nomination for president. […] along with […] Kathleen Cleaver’s campaign for the California State Assembly.” (Bloom 2016, 124)

05.20.1968 — “On May 20, [1968] the Black Panther Party held a benefit performance at the Fillmore East in the East Village [New York] to help raise $200,000 bail for Eldridge Cleaver and six other Panthers arrested in the April 6 shootout in Oakland. The benefit, which featured several plays and performances by Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Ed Bullins, drew twentysix hundred people. James Forman of SNCC was the event’s emcee, and Kathleen Cleaver spoke about Lil’ Bobby Hutton’s martyrdom and her husband’s case.” (Bloom 2016, 149)

07.1968 — “In July, the SDS convention passed a major resolution in support of the Black Panthers asserting that “Huey must be set free!” They pledged to “give full support, in whatever manner is needed,” both to free Huey and to support the Panthers generally.” (Bloom 2016, 134)

07.14.1968 — “Bobby Seale speaks at a “Free Huey!” rally in “Lil’ Bobby Hutton Park” on July 14, 1968. The bus and sound system were on loan from the Peace and Freedom Party. James Forman (seated middle) and Chief of Staff David Hilliard (seated right) share the stage with Seale. (© 2011 Pirkle Jones Foundation / Ruth- Marion Baruch)” (Bloom 2016, 170)

07.15.1968 — “Monday July 15 marked the opening day of Huey Newton’s trial on charges of murdering a police officer. The Panthers argued that Newton, not Officer Frey, was the one who had been attacked and that the trial was yet another act of political repression. They brought their case to the court of public opinion, organizing a rally in front of the imposing granite Alameda County courthouse in Oakland that morning.” (Bloom 2016, 135)

08.1968 — “When [George Mason] Murray [Black Panther Minister of Education] traveled to Cuba in August 1968 to promote the “Free Huey!” campaign [and to represent the Black Panthers at a conference sponsored by the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL)], leaders of anticolonial and revolutionary movements around the globe embraced the Panthers.” (Bloom 2016, 270)

08.25.1968 — “On August 25, the Panthers held a rally at De Fremery Park in west Oakland that they ceremoniously renamed Bobby Hutton Memorial Park in honor of the martyred Panther youth.” (Bloom 2016, 125)

08.1968 — “The Democratic nomination and the party’s position on Vietnam would be decided at the Democratic National Convention that August in Chicago. […] Organizers also invited the Black Panthers to speak. In late August [1968], Bobby Seale and David Hilliard flew to Chicago.” (Bloom 2016, 207) At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Bobby Seale was arrested and charged with conspiracy and inciting riot outside of the convention.

“By the fall of 1968, membership in the Black Panther Party was mushrooming. […] As Party membership and influence grew, so did repressive action by the state. The Party sought meaningful activities for members that would serve the community, strengthen the Party, and improve its image in the public relations battle with the state. In this context, community programs quickly became a cornerstone of Party activity nationwide.” (Bloom 2016, 181)

“By the fall of 1968, as the Party became a national organization, it had to manage the political ramifications of actions taken by loosely organized affiliates across the country. The Central Committee in Oakland codified ten Rules of the Black Panther Party and began publishing

them in each issue of the Black Panther.” […] “The Party insisted that Panthers use weapons only against “the enemy” and prohibited theft from other “Black people.” But they permitted disciplined revolutionary violence and specifically allowed participation in the underground insurrectionary “Black Liberation Army.” (Bloom 2016, 343)

“SDS published Newton’s ideas about the white New Left as a pamphlet and distributed it nationwide that fall [1968], in coordination with “Free Huey!” actions. (Bloom 2016, 297)

“But by the fall of 1968, the FBI was secretly developing what would become its most intensive program to repress any black political organization. Of 295 actions initiated by the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program to destabilize black nationalist organizations, 233 of them — or 79 percent — targeted the Black Panther Party.” (Bloom 2016, 210)

09.1968 — “While the FBI did not mention the Black Panther Party in earlier COINTELPRO memos targeting black nationalist organizations, the agency now [September 1968] began to focus its attention on the Panthers.” (Bloom 2016, 203)

09.08.1968 — “On Sunday night September 8, 1968, Newton was convicted of manslaughter in the killing of Officer Frey and sentenced to two to fifteen years in prison.” (Bloom 2016, 199)

09.10.1968 — “About thirty hours after Newton’s conviction, at 1:30 in the morning on September 10, two white on-duty uniformed police officers shot up the windows and office of the Black Panther headquarters at 4421 Grove Street in Oakland.” (Bloom 2016, 199)

10.28.1968 — “On October 28, 1968, the one-year anniversary of Huey Newton’s incarceration, Donald Cox, field marshal of the Black Panther Party, and a contingent of five other Panthers visited San Francisco State. Murray called a BSU rally.” (Bloom 2016, 273)

11.01.1968 — “While [Bobby] Rush and [Fred] Hampton teamed up in June 1968, the Black Panther national office did not officially recognize the chapter until October, and the first Chicago office was not opened until November 1, 1968.” [Bloom 2016, 231]

11.05.1968 — “On November 5, by the thinnest of margins, Nixon was elected the thirty-seventh president of the United States. From the first days of his presidency, Nixon took a personal interest in repressing the Black Panther Party.” (Bloom 2016, 210)

11.28.1968 — “After the loss of Bobby Hutton, Eldridge [Cleaver] was ordered to surrender to San Francisco Police to go back to prison, but on November 28, 1968, he didn’t turn himself in, and he was not to be found. […] He had gone to Algeria.” — Kathleen Cleaver (Nelson, 2015)

11.29.1968 — “On Friday November 29, 1968, fifteen hundred delegates from throughout the Americas gathered in Montreal for the Hemispheric Conference to End the War in Vietnam. […] The Black Panther Party sent a delegation led by Bobby Seale and David Hilliard and including a dozen rank-and-file Panthers from various chapters.” (Bloom 2016, 309)

12.25.1968 — “After Eldridge Cleaver went underground in the late fall of 1968, he clandestinely traveled to Cuba, arriving on Christmas day. [December 25, 1968]” (Bloom 2016, 314)

“By 1968 the Black Panther Party was established as the most prominent Black Nationalist organization, and its newspaper the Black Panther had a weekly circulation of more than 100.000 copies.” (Vincent, 2013, p190). “[…] [Y]oung activists from around the country contacted the Party asking how they could join, and the Party responded by opening new Black Panther offices in Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and at least seventeen other cities by the end of the year [1968], including Albany, Bakersfield, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Des Moines, Detroit, Fresno, Indianapolis, Long Beach, Newark, Omaha, Peekskill, Philadelphia, Richmond, Sacramento, and San Diego.” (Bloom 2016, 159)

1966/67 « » 1969

A Sampled History 1966/67, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972/82.