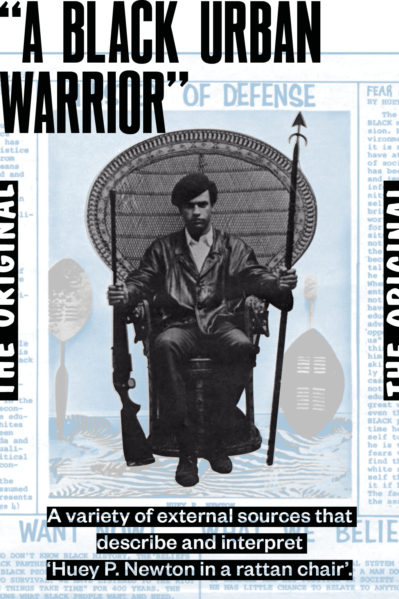

In this section, we present a variety of external sources that describe and interpret ‘Huey in a rattan chair’. Between all these sources, the significance of the iconic image rises to the surface.

“Three days after the Sacramento action [May 2, 1967], Huey and Bobby [Seale] began to work with [Eldridge] Cleaver on the second issue of the Party’s paper, which would be the first full-format edition. They laid out the paper at Beverly Axelrod’s house [a civil rights attorney who represented Cleaver and later the Black Panther Party] in San Francisco. […] [T]he Panthers called in a radical white photographer [possibly Blair Stapp] who brought over his camera and tripods to take the pictures for the issue. For the photoshoots, Eldridge brought in the zebra-skin rug, rattan chair, and African shield and composed the famous picture of Huey P. Newton on his wicker throne.” (Bloom, 2016, 80)

“The leader and defender of the black colony in the white motherland America” — Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin, 2016

“Above the Ten Point Program, under the head-line “Minister of Defense,” the Black Panther carried a photo of Huey that serves to announce to the world that the vanguard of Black Power had arrived. In the photo, Huey is seated and facing the camera. His forehead, nose, and left cheekbone are well illuminated, whereas the right side of his face is obscured in shadow, capped by the trademark black beret tilted at a precise angle to cover the top of his right ear. His slacks, shoes, and leather jacket are also black, his pressed shirt light colored—the standard Black Panther uniform. He sits comfortably but alert, his feet positioned, ready to stand. Behind him is the ornate fan of the wicker throne in which he sits. A handful of live ammunition sits in a small pile on the ground near the butt of the rifle he holds in his right hand. Like the zebra-skin rugs on the floor and the two shields behind him, the tall black spear in his left hand suggests Africa. The photo announces Huey as leader and defender of the black colony in the white motherland America.” (Bloom, 2016, 73)

“This image of Huey P. Newton, a founder of the Black Panther Party, appeared in the first official issue of The Black Panther – Black Community News Service. Fellow Panther Eldridge Cleaver selected props such as the zebra skin rug and Zulu shield to evoke the fearless leadership of a warrior king. Newton was even seated in a throne-like rattan ‘peacock chair, spear in one hand, shot gun in the other. The image of an African American man armed defensively was a powerful statement of intent in marked contrast to the nonviolent campaigns for integration. Elaine Brown, who led the Black Panther Party from 1974-1977, said the photographic poster of Newton had been her ‘introduction to revolutionary art’.” (Soul of a Nation, 2017)

“An angry successor to Malcolm X – the street gang leader come to politics” — Tim Findley, 1972

“There was one best understood image of Huey Newton at that time which appeared everywhere in posters and buttons — Newton seated rigidly in the wicker chair of African kings, his beret drawn down over one eye, one hand gripping a shotgun and the other a spear. […] Newton disliked it and even before he left prison ordered it discontinued. The seething image of black revenge stuck, however, portraying Newton as an angry successor to Malcolm X — the street gang leader come to politics.” (Findley, 1972)

“A BLACK URBAN WARRIOR! A Black Panther! — Kathleen Cleaver, 2018

Kathleen Cleaver: “This is a Black Panther, so there’s a lot of African symbolism […] it looks like a warrior”. Emory Douglas: “An urban warrior!” Cleaver: “A BLACK URBAN WARRIOR! A Black Panther!… This was early, the Black Panther Party was very small when this picture was taken”. (All Power to the People!, 2018)

“Newton is not an object controlled by Western colonists, […] he acknowledges the centuries-long history of colonialism and threatens to break down the system itself.” — Anna Gedal, 2015

“Newton proudly poses on his rattan throne: spear in one hand, rifle in the other. His expression is stern and his gaze meets the eye. The photo at once mocks Western colonialist portraiture—the zebra rug, the unambiguously “tribal” props in the background, but this stops at Newton. And it is with him that this photo turns the genre’s stereotype on its head. Newton is not an object controlled by Western colonists: he is a crusader against it. Newton is ferocious. Newton is a warrior. In this portrait, he acknowledges the centuries-long history of colonialism and threatens to break down the system itself.” (Gedal, 2015)

“The poster was made from a photo taken by Eldridge Cleaver in 1967 at attorney Beverly Axelrod’s house. Eldridge made the original posters and then gave them to the Black Panther Party to sell. It quickly became the leading poster of its time and was sold throughout the world. The poster is a symbol of man’s evolution in self-defense, from the spear and shield to the shotgun.” (Oakland Museum of California)

“This is one of the most iconic images of the Black Panther Party – Minister of Defense Huey Newton seated in a wicker chair, holding a spear and a bolt-action shotgun, surrounded by Africana. The scene was composed by Eldridge Cleaver. Newton is holding an unusual firearm, a bolt-action box-magazine shotgun, most likely a Mossberg model 485. When the photo was recreated for the 1995 film “Panther” (directed by Mario Van Peebles and starring Marcus Chong as Huey Newton) they substituted a much more standard .30 caliber M1 carbine, but still scattered shotgun cartridges next to the rifle as in the original photo.” (Oakland Museum of California)

“And while the defiant image of the group resonated with a lot of young people (a poster of Newton in a rattan throne, a spear in one hand and a rifle in the other, adorned many a dorm room wall), it clearly scared the hell out of the authorities.” (Elder, 2016)

“Huey as ’Black Warrior Prince’ speaks to the initial masculine identity of the Party.” — Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin, 2016

“[T]he man’s revolutionary role [was presented] as central and the women’s revolutionary role as supportive. This patriarchal orientation of Black Panther politics, common to most black nationalist and other movement organizations at the time, is evident throughout the Party’s early actions and communications. Telling contrasts, such as the iconic representation of Huey as “Black Warrior Prince” set against the relatively obscure representation of the Panther woman as “Woman Warrior,” speak to the initial masculine identity of the Party.” (Bloom, 2016, 97)

“A mythical figure, a godly photograph of a man, or a man’s image of God. […] A homegrown messiah.” — Elaine Brown, 1994

“Huey had gone to prison within the first year of the party’s formation. During the three years in prison, his small essays on revolution, printed and distributed in pamphlet form, had been required reading for party members, as his rattan-chair poster had been our introduction to revolutionary art. Thousands had joined the Black Panther Party while Huey was behind bars. To them he was a mythical figure, a godly photograph of a man, or a man’s image of God.” (Brown, 1994, 251)

“For those who had known him on the streets of Oakland […] Huey’s mythical persona had supplanted the street image of “crazy Huey”, the man they had known in pre-Panther days. He had become a kind of homegrown messiah.” (Brown, 1994, 252)